Joe Cortright believes if the Coast Guard bridge permit — which is required to start construction — is delayed into 2027, this could be a death blow for the I-5 Bridge replacement project

Joe Cortright

City Observatory

You can’t build a bridge across a navigable waterway in the United States without a permit from the US Coast Guard.

The Coast Guard has always been clear that it wants a 178 foot clearance over the Columbia River for any new crossing. With any shorter proposal, the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBR) is legally “proceeding at its own risk.”

The Interstate Bridge replacement project has always believed it could bully the Coast Guard into approving a much lower fixed span, and its combination of arrogance and hubris have delayed, and once again threaten to kill this project.

The IBR is years behind schedule with its environmental review and has as yet failed to submit a new navigation impact report which it needs to trigger a Coast Guard reconsideration of the navigation requirements.

The IBR project schedule says it will take more than 16 months from the filing of a new navigation impact report until they receive a bridge permit, which would push the project start well into 2027.

One of the things that helped kill the Columbia River Crossing more than a decade ago was nearly two years of delay in re-designing the project to comply with Coast Guard navigation requirements. State DOT officials thought they could bully the Coast Guard into agreeing to their preferred 95-foot clearance bridge, but the Coast Guard insisted that 116 feet was the minimum necessary. It took close to two years and tens of millions of dollars to re-design the bridge and approaches, and by then, political support for the project had collapsed.

Once again, it appears that the navigation clearance issue is about to torpedo the bridge. The state DOTs have been claiming that 116 feet would be enough, but in 2022, the Coast Guard issued a Preliminary Navigation Clearance Determination” or PNCD, that IBR that it would need to build a crossing (bridge or tunnel) with a minimum of a 178 foot vertical clearance over the Columbia River.

IBR officials have always been confident that they would get the Coast Guard to eliminate the 178-foot clearance requirement and allow them to build a much lower fixed span. Program Administrator Greg Johnson said he believes a fixed-span bridge will ultimately end up spanning the Columbia. He said a movable span would likely cost $500 million more than a fixed-span bridge and noted that the Columbia River Crossing project received a record of decision from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transportation Agency for a fixed-span bridge with the lower river clearance.

“I would be totally shocked if we can’t get to a fixed-span,” Johnson said.

Since then, IBR has been working – very slowly – to assemble evidence that the Coast Guard should require only a 116-foot clearance. The project has been working on a “navigation impact report” which describes the economic impacts of constricting commerce and development because of a low clearance bridge across the river.

IBR has delayed providing a new “Navigation Impact Report (NIR)” to the Coast Guard

IBR appears to be waiting until the last possible minute to file this report and ask for a bridge permit, in order to create political pressure to force the Coast Guard to approve the project rather than delay or kill it.

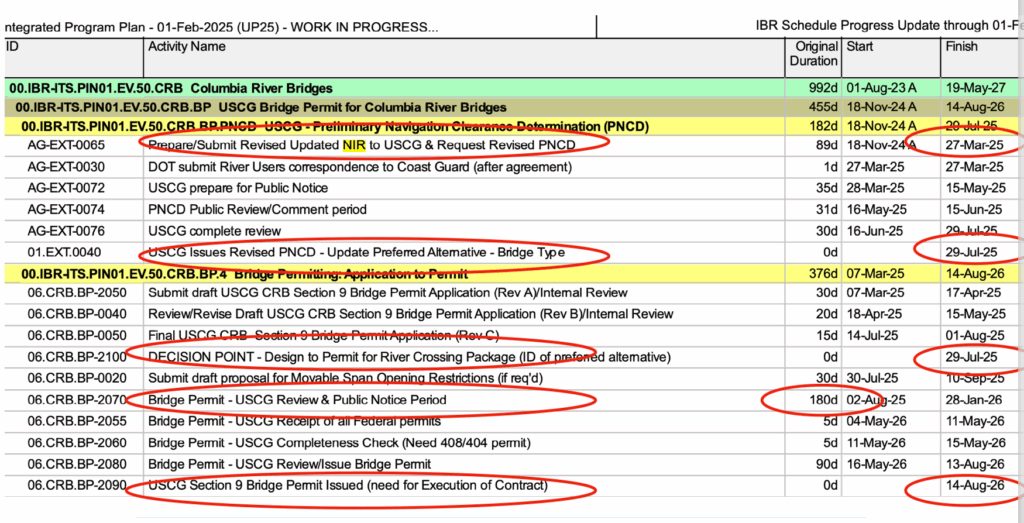

IBR’s February, 2025 schedule called for a Navigation Impact Report to be submitted to the Coast Guard by March 27, 2025, and a new determination of navigation clearance by July 29, 2025, which would allow the IBR to select a definitive design for the new bridge (either a 116′ foot clearance fixed span or a moveable span with the 178′ clearance).

At the September 15, 2025 meeting of the Joint I-5 Committee, project officials disclosed that they haven’t even submitted the new NIR to the Coast Guard. Greg Johnson testified:

“So to start that process, we’re looking to submit an updated navigational impact report to the Coast Guard . . .”

It’s important to note that the NIR and the bridge permit are critical to the timing of the IBR project. According to IBR’s project schedule, construction cannot begin on the project until after they receive the Coast Guard issued bridge permit. According to the project schedule, the process of seeking a permit for their preferred 116-foot clearance requires 120 days between the time IBR submits an NIR and the time the Coast Guard would issue a “Revised PNCD” and a further 13 months for the Coast Guard’s internal and public review of the Bridge Permit. That means it takes about seventeen months from the time a NIR is filed until a bridge permit is issued. (IBR’s February, 2025 schedule called for the NIR to be filed on March 27, 2025 and the Bridge Permit to be issued more than 16 months later on August 14, 2026. That means if the NIR is filed in January 2026, we wouldn’t expect a Bridge Permit to be issued for a further 16 months, or in mid-2027.

According to the IBR’s February 2025 schedule, they had planned to submit the updated NIR by March 27, 2025; according to testimony at the September 15, 2025 legislative oversight committee, they have yet to submit this report to the Coast Guard. That means that they are already about six months behind schedule.

Coast Guard, 2022: 178 feet; anything less: “proceed at your own risk.”

The IBR has known for more than three years that the Coast Guard would require a 178-navigation clearance, and advancing any other alternative meant that the two state DOT’s were “proceeding at their own risk.” The IBR project is basically asking the Coast Guard to vacate this decision, something that seems increasingly unlikely, especially as IBR has failed to submit a new navigation report that would be needed for the Coast Guard to even begin reconsidering.

The Coast Guard issued its Preliminary Navigation Clearance Declaration saying a 116-foot fixed span bridge would unreasonably impede river navigation:

“Our PNCD concluded that the current proposed bridge with 116 feet VNC [vertical navigation clearance], as depicted in the NOPN [Navigation Only Public Notice], would create an unreasonable obstruction to navigation for vessels with a VNC greater than 116 feet and in fact would completely obstruct navigation for such vessels for the service life of the bridge which is approximately 100 years or longer.’’ – B.J. Harris, US Coast Guard, to FHWA, June 17, 2022, emphasis added.

Deja Vu all over again

A too low bridge design led to delay and failure of the Columbia River Crossing.

More and more, the IBR seems bound and determined to repeat exactly the mistakes the led to the failure of the Columbia River Crossing. A decade ago, the Oregon and Washington transportation departments tried to force the Coast Guard to agree to a fixed Columbia River Crossing I-5 bridge with a height of just 95 feet over the river, arguing (exactly as they are now) that this lower level best balances the needs of different forms of transportation. Balancing the needs of road users, though, is not the legal standard applied by the Coast Guard, which following federal law, prioritizes the needs of river navigation. In 2012, a year after the CRC “Record of Decision” the Coast Guard simply denied the request for a 95 foot clearance span. Here’s the headline from the Vancouver Columbian from 2012.

The two DOTs attempting to force the Coast Guard to agree to a lower bridge height added more than a year of delays to the CRC process (which ultimately failed) as well as millions of dollars in added planning costs.

With the revived “Interstate Bridge Replacement” the two state DOTs have again attempted to force the Coast Guard to agree to a low fixed span. IBR has obstinately insisted it would build a fixed span vastly lower than the Coast Guard demanded, and then repeatedly delayed the process for asking the Coast Guard to revise its decision. IBR is obviously trying to “run out the clock” and pressure the Coast Guard to go along with the highway department’s preferred lower design. It is a high stakes gamble that is again backfiring.

Under the Trump Administration, these delays could easily be fatal. Trump DOT officials are slow-rolling the processing of Biden Administration highway grants, and if they don’t get the project started by September 2026, IBR stands to lose out about $2.1 billion in awarded federal grants. If the Coast Guard bridge permit — which is required to start construction — is delayed into 2027, this could be a death blow.

Also read:

- C-TRAN board increases salary for CEO Leann CaverC-TRAN CEO Leann Caver received a 2.5 percent raise as the board recognized her leadership and celebrated rising ridership numbers after years of recovery.

- Clark County March storm response information and closuresClark County Public Works is responding to reports of flooded roads and parks, with closures and safety advisories in effect as heavy rains impact the region.

- C-TRAN: Light rail funding addressed again; changes are coming to C-TRAN board compositionC-TRAN approved new language tied to the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program that shields smaller cities from light rail operating costs while shifting potential financial responsibility toward Vancouver and the urban growth area.

- City of Washougal advances overcrossing design for 32nd St Rail Crossing ProjectWashougal officials have selected an overcrossing design for the 32nd Street Rail Crossing Project, aiming to improve safety and reduce traffic delays caused by frequent train blockages.

- Opinion: Trails, roadways and crosswalksDoug Dahl explains how Washington law treats hiking trails that cross roadways and whether pedestrians automatically have the right-of-way.