New transportation corridors key to reducing regional traffic congestion

Members of the Clark County Council have weighed in on the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program (IBRP) project, making recommendations a month after members of the Vancouver City Council made their desires known. Their focus was on improving traffic congestion and the movement of freight. The County Council members rejected tolling as a means to pay for the project, and rejected light rail as a form of mass transit. The council members said tolls “would have a negative impact on all Clark County residents, particularly those with low income.”

The 3-2 vote occurred during a Council Time discussion last Wednesday (Sept. 22). This followed an initial discussion on Aug. 4 where ideas were shared and discussed by the council.

All five councilors supported the bridge replacement project, but Councilors Temple Lentz and Julie Olson voted against the resolution, indicating displeasure with some of the language.

“Saying that we are against all tolls, I think is also not engaging in a reality-based discussion,” Lentz said.

Councilor Karen Bowerman led the effort, introducing a two and one half page set of issues and concerns at the August Council Time discussion. “There is one primary goal associated with the bridge replacement project that rises above various secondary goals, and that is to significantly reduce traffic congestion.”

“We really should make a public statement about what really will bring relief from freight mobility, to reducing our carbon footprint, and reducing transit time,” Councilor Gary Medivigy said during the initial discussion in August. “We’re only going to ever get to that if we can plan, design and fund another corridor.”

It has been over 40 years since a new transportation corridor was built, yet the regional population has doubled, along with the number of cars on the road. Three years ago PEMCO revealed that 94 percent of people in the Portland and Seattle areas prefer to use their cars. Moody’s recently predicted a permanent 20 percent reduction in transit ridership nationwide.

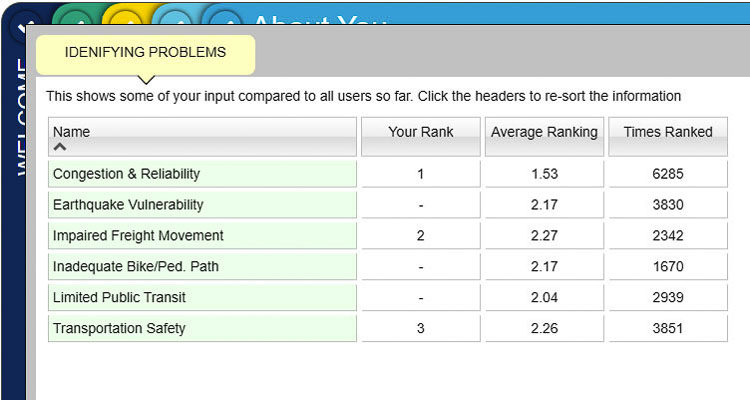

Bowerman remained focused on traffic congestion relief. People on both sides of the river have overwhelmingly asked to reduce traffic congestion in numerous surveys over the past few decades. It was the top IBRP issue getting nearly 50 percent more votes than the next two issues. The 2021 IBRP online survey of the people found “congestion and reliable travel times” received 6,285 votes, whereas transportation safety and seismic concerns got just over 3,800 votes.

The council resolution cited INRIX 2018 and 2020 surveys showing the Portland metropolitan area has the eighth worst traffic congestion in the nation. Over two-thirds of area residents agree we cannot “wait any longer to develop plans to help fix our region’s long-term challenges with traffic and transportation.”

The language opposing tolls as a means to pay for the project triggered the fiercest discussion. Lentz accused the others of “ignoring reality.” Yet the others point out how that policy creates “roads for the rich” (in reference to Vancouver Councilor Bart Hanson’s description) because congestion pricing could make regular crossing of the bridge prohibitively costly. Clark County voters have repeatedly voiced their opposition to tolling, especially in the failed Columbia River Crossing (CRC).

The council supported mass transit, but the majority focused on having vehicles share a lane with C-TRAN buses until transit demand rose to a point that enough buses traveled the corridor to justify having their own lane.

“Provide a high-capacity dedicated guideway lane for C-TRAN’s bus rapid transit when ridership is greater than or equal to 2,000 vehicles per hour in one lane devoted to auto and bus traffic. If ridership is less than 2,000 vehicles per hour, C-TRAN bus rapid transit should be accommodated in a manner that does not contribute to additional traffic congestion,” the resolution said.

Transportation architect Kevin Peterson has previously shared that an average highway lane can handle about 2,000 vehicles per hour. Bowerman indicated she didn’t want a dedicated transit lane to sit empty and unused, decreasing capacity while other vehicles might be stuck in a traffic jam.

Council Chair Eileen Quiring gave a further example of the Portland HOV lane. It is a general purpose lane all day for all vehicles to use except during rush hour, where two-passenger vehicles and transit can share the HOV lane during a limited three-hour period.

C-TRAN recently announced it would be cutting its cross-river express bus service nearly in half, due to declining demand. Prior to the pandemic, it had seven separate express bus lines, five serving the I-5 corridor and two serving the I-205 corridor. Ridership on the express bus lines had been declining for several years, dropping below 1,000 people a day during the pandemic.

Citizens’ concerns cited by Bowerman, included a survey indicating “seventy-seven percent felt “maximizing bridge lanes to carry more vehicles” is very to extremely important whereas only ten percent said that was not important.” IBRP administrator Greg Johnson has already stated his team is proposing only three through lanes on the replacement bridge.

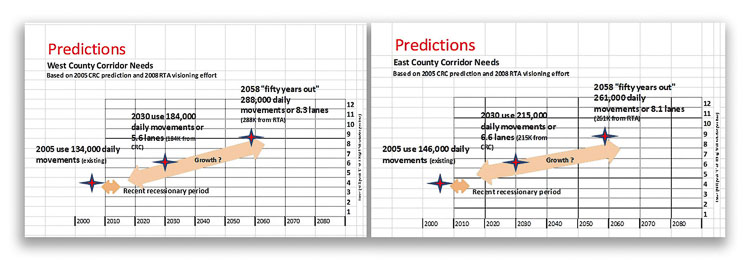

“Two additional bridges were envisioned by RTC given traffic projection numbers and in 2060, they expected in excess of 288,000 average daily vehicle movements for the I-5 corridor,” was the council’s reference to Peterson’s analysis of the Regional Transportation Council’s 2008 “Visioning Study”.

Councilor Bowerman shared the following with Clark County Today via email.

“Those of us Councilors voting in favor of the Resolution were criticized by another Councilor for ‘not engaging in a reality based discussion.’ One of our constituents among the thousands who commute to Portland for work was listening to our recording and picked up on that phrase and said he wanted to share some of his own reality!

“He wrote me that every Clark County resident that works in Oregon and who has to commute over the I-5 bridge IS ALREADY PAYING A TOLL that is called Oregon State income tax at the rate of 9%. Given that the average Vancouver WA resident makes only $32,300 per year, he wrote, a 9% income tax on that amount is $2,900 per year or $242 per month.

“Most if not all of those commuting to Oregon are probably earning more than the average, and therefore paying more to the State of Oregon. Not a single Clark resident, he said, has any representation for that taxation if we Councilors won’t do it.’’

The resolution calls for planning two new transportation corridors. “Allow for, and encourage, development of a third and fourth corridor crossing the Columbia River between Washington and Oregon,’’ Bowerman stated.

“We know that Portland does not want additional lanes at the Rose Quarter, and not 10 lanes in each direction at the Rose Quarter by 2060, building a third corridor now and planning for a 4th bridge is critical,”Bowerman wrote in her discussion document.

This triggered an extensive four-way discussion between Medvigy, Bowerman, Olson and Lentz during the August meeting.

“No matter how many lanes you put on the I-5 bridge, with the entire corridor especially the Rose Quarter and through other areas in Portland, it is just maxed out.,” Medvigy said. “The only way to get to it (congestion relief), is to plan another corridor as has been envisioned more than 20 years ago.”

“We are so far behind in the Greater Portland, Vancouver metropolitan area,”Medvigy said. “You look across the nation, we have some of the worst congestion from a freight mobility point of view.“

Councilor Olson pushed back. “This conversation is old and tired. It has been had for the last 10 years. The replacement I-5 bridge is the priority.”

“The reason why is because of the goal of reducing traffic congestion,” responded Bowerman. “Until a replacement project would add significantly to the number of lanes going across the Columbia, they are therefore related topics. So far we’ve heard a reluctance to add additional lanes for automobile traffic, which does not do anything to improve traffic congestion.”

Lentz responded that many of the premises were flawed. Additional lanes create induced demand, which actually increases traffic congestion, she said.

“We need to recognize that we can add a ton of bridges and a ton of crossings, but where people are going is still largely the same,” Lentz said. “So there will continue to be congestion along the I-5 corridor, because that is where most of the economic activity is.”

That is contrasted by Portland having a dozen bridges across the Willamette River.

“I think it is much more forward thinking to try to figure out ways to give people reliable travel times in the near term future while also thinking much more creatively about how people get around our region, than continuing to rely solely on single passenger vehicles,” she said.

“Counselor Lentz, there isn’t a single word that you said that I disagree with,” Medvigy responded. “It’s just that to be forward thinking, and we’re already 20 years behind, the additional capacity will come from a circular route, something that goes from Longview to Salem, something that is a bypass, a true bypass that almost every other metropolitan area in the nation has. We don’t have it.”

Medvigy took a larger view — the I-5 and I-205 are part of a single, north-south transportation corridor for the entire west coast. He referenced the fact that we haven’t added another corridor to bypass downtown Vancouver and Portland in decades.

“Not everyone goes to Vancouver or Portland,” he said. “Some people just want to drive to the north or to the south or to the east or west.”

The resolution will be given to Johnson’s IBRP team, where they already have input from the Vancouver City Council and many other metro area governments.

Medvigy shared more on the tolling issue, via email.

According to the Bureau of Transportation statistics, there are 140 toll bridges in the USA. The Department of Transportation — classifies 57,627 bridges as “Principal Arterial – Interstate” (25,231 urban and 32,396 rural), out of more than 600,000 bridges total. So, only 0.25% of the bridges which the feds define as “principal” are toll bridges.

Medvigy even went as far as to adjust the length of the bridge to one mile or more and came up with 296 bridges. “Toll bridges aren’t the norm,” he said.

WSP USA, the primary consultant to the IBRP delivered the Arthur Ravenel bridge in Charleston without tolls in 2005. The 13,200 foot long bridge has eight 12-foot lanes for traffic, provides 186 feet of clearance for marine traffic, and offers a bike/pedestrian facility. The cost was $632 million of which $12.million was for the bike/pedestrian facility. The federal government provided $96.5 million, none of which was for transit.

In the failed CRC, forensic accountant Tiffany Couch reported that the $3.5 billion project would have an additional $2 billion in debt service costs and toll collection costs, bringing the total cost of the CRC project to approximately $5.5 billion.

“According to the CRC’s finance plans, an additional $2.0 billion in tolls will need to be collected for the aforementioned debt service and bridge operation and maintenance costs,” she wrote. This was required to pay off an estimated $1.5 billion in borrowed money.

Couch also reported the cost of the actual bridge was $791.3 million.

Recently, the Washington legislature had to bail out tolling facilities WSDOT administers. The significant reduction in traffic due to the pandemic lockdown caused tolling revenues to drop below the costs to run the facilities. The I-405 toll lane revenue dropped 81 percent. Total revenue was $128 million below forecasts for the state.

The price tag and the design of the bridge replacement project is not known. Last year the IBRP told Oregon and Washington legislators if they were to build the CRC bridge today, it could cost between $3.2 billion to $4.8 billion, depending on whether light rail or bus rapid transit were included, and high and low cost scenarios.