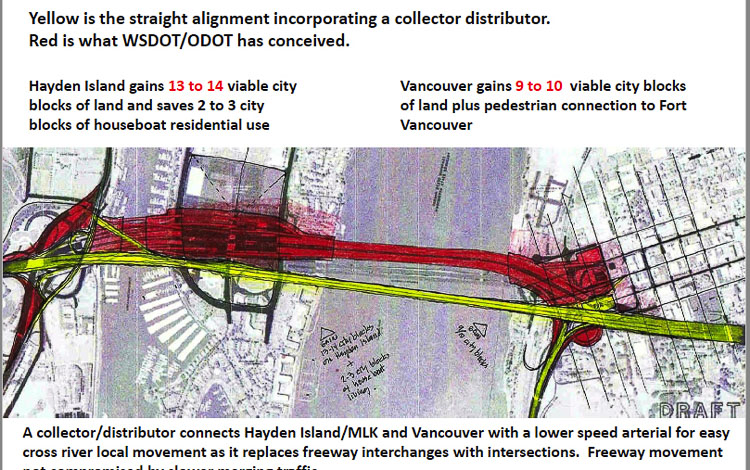

Straight alignment and collector-distributor model uses less land and provides larger turn basin for marine traffic

A decade ago, Clark County citizens followed the ups and downs of the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) with varying levels of interest and concern. The $3.5 billion project was initially “a bridge too low.” Engineers at Washington State University evaluated the initial plans and reportedly said it was not buildable.

As the current Interstate Bridge Replacement Program moves forward, members of the public are waiting for specific plans of the project to be revealed to determine how closely the project will mirror the CRC.

There were multiple issues related to the height of the bridge and Pearson Field in addition to what was needed for marine traffic on the Columbia River. Barges have to call for a bridge lift when fast moving river current makes the “S curve” with the BNSF rail bridge impossible for them to safely complete.

From a traffic congestion perspective, the current Interstate Bridge’s biggest problem (besides not enough lanes), is that there are three interchanges within a 1.5-mile area of the bridge and four interchanges within two miles. These are Mill Plain, SR-14, Hayden Island, and Delta Park/Expo.

Normal freeway design parameters call for a minimum spacing between interchanges of one mile in urban areas and three miles in rural areas.

The CRC did not solve this problem. The Chairman of the Bridge Review Panel, Tom Warne provided the following statement to WSDOT during the CRC debate.

“As a panel we did feel (the need) to communicate that the interchange spacing and ramp configurations as presented by the CRC at the time of our work were unprecedented. We noted several times that other DOTs were doing all they could to eliminate such spacing and configuration issues while this project was perpetuating them.”

Kevin Peterson is a transportation architect who entered the discussions over a decade ago. He has lived in many international cities as he helped them design transportation solutions for both transit systems and automobiles. He scrutinized many of the details related to the CRC for both vehicle and freight traffic and shared those details with citizens at multiple forums and town hall events.

In early 2010, Peterson was asked to look at the CRC project by architects who were very concerned with the proposed intrusive design. “Why was the project not pursuing a straight alignment,” he asked. “Why is the project using massive land-hungry interchanges? Why is the project not considering a collector/distributor to separate and serve shore to shore travel needs?”

He discovered that a straight alignment with a collector/distributor is possible. This was shared with WSDOT/ODOT in late spring 2010, only to be promptly ignored.

Peterson shared two critical design efforts or flaws that perhaps contributed to the project’s failure. One was using an incorrect glide path assumption for Pearson Field which triggered unnecessary restrictions on bridge height and apparently was the reason the freeway alignment was shifted downstream. The other was the failure to use what he describes as a “collector-distributor” (C-D) model for the freeway design, which contributed to the lack of improvement in travel times.

He also spoke about concurrency. “Planners realize that without coordinating projects, you would end up with a five-inch pipe plugging into a three-inch pipe, and the five-inch pipe would do you no good,” Peterson said. Expanding the bridge to five lanes would do no good if the two-lane Rose Quarter were not addressed.

Peterson emphasized the carrying capacity of the entire corridor is what should be discussed by transportation officials on both sides of the river. He was stunned to learn that there had only been two planning studies for future transportation needs, both were done by Washington entities. One was the 2008 RTC (Regional Transportation Council) Visioning Study and the other was done for the CRC.

Improper Pearson Field glide path

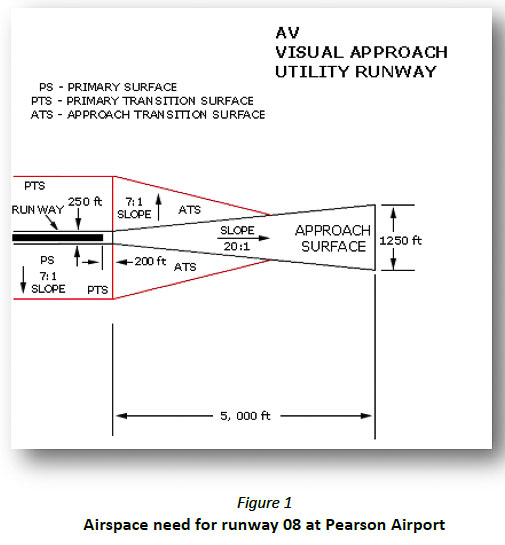

The CRC project office made a mistake with respect to the glide path required for Pearson airport, according to Peterson. The project office design incorporated a 34:1 glide path when they should have used a 20:1 glide path.

This error reduced the available vertical envelope for I-5 by 36 feet just upstream of the existing bridges. One consequence of this error was a two-level freeway on a straight alignment just upstream of the existing I-5 bridge was deemed not to fit. Using the correct angle for a utility runway at Pearson allows the bridge alignment to be straightened.

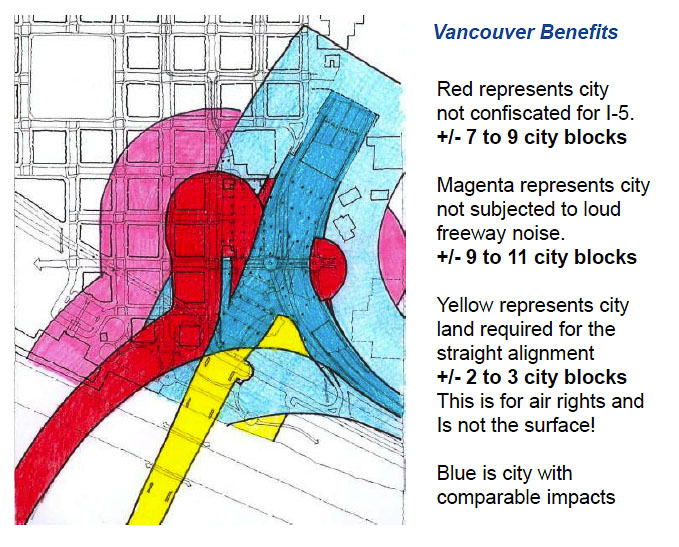

Removing the “kink” in the freeway has many advantages. It moves the freeway away from the urban core of downtown Vancouver. It widens the turn basin for marine traffic. A straight alignment also allows for many types of bridge options

Furthermore, a straight alignment requires as little as 1,620,000 square feet of land with 1,270,000 on Hayden Island and urban Vancouver. The present bridge occupies about 2,560,000 square feet of land with about 1,750,000 on Hayden Island and urban Vancouver. The straight alignment with a lower level C-D would use over one third less land than the present bridge occupies.

The CRC proposal required 4,125,000 square feet of land with about 2,820,000 on Hayden Island and urban Vancouver. That was 60 percent more land than the present bridge occupies, and two and a half times more land than a straight alignment might require according to Peterson’s calculations.

Additionally, Peterson noted that roughly 20 city blocks of land would be freed up on Hayden Island and in downtown Vancouver by embracing a straight alignment. The huge bridge footprint on Hayden Island was the biggest concern of the local community during the CRC debate.

A straight alignment would offer several benefits to marine traffic on the Columbia River.

The turn basin between the BNSF rail bridge and the current Interstate Bridge could be extended by an additional 700 feet in length. The CRC proposal reduced the turn basin and significantly increased the footprint of the bridge in and over the water.

Additionally, the CRC failed to achieve a 125-foot clearance for marine traffic put forth by industry leaders, nor the recommendation of 135 feet put forth by the Coast Guard. Peterson believes his options would allow for up to 142 feet of clearance.

Collector-distributor needed

Collector-distributor (C-D) roads are extra lanes between the freeway mainlanes and city streets. Their primary purpose is to “move vehicle lane-changing away from the high-speed traffic on the freeway mainlanes”. Lane changes occur on the C-D roads as vehicles move from the freeway to the frontage road or other connecting roadways (and vice versa).

C-D facilities can be used to:

• Allow a single freeway exit ramp to feed vehicles into two or more crossing roadways.

• Collect vehicles from several crossing roadways so that they can enter the freeway at a single entrance ramp.

The concept Peterson offered was a two-deck bridge. The upper deck would carry traffic in both lanes at fast-moving freeway speeds over the Columbia River with no merging or exiting traffic.

The lower deck would serve as the collector-distributor. It would travel at slower, perhaps 45 mph speeds, allowing vehicles to enter or exit the lower level in a safe and efficient manner. It would also have pedestrian and bicycle lanes and could be used for transit. The C-D would connect urban areas on both shores much like any other city arterial.

Together, they would offer more capacity across the river while consuming less land for the bridge footprint. The Interstate Bridge currently handles between 5,000 and 6,000 vehicles per hour at peak commute times. Peterson says his design could handle 9,000 or more vehicles per hour; a 60-80 percent increase.

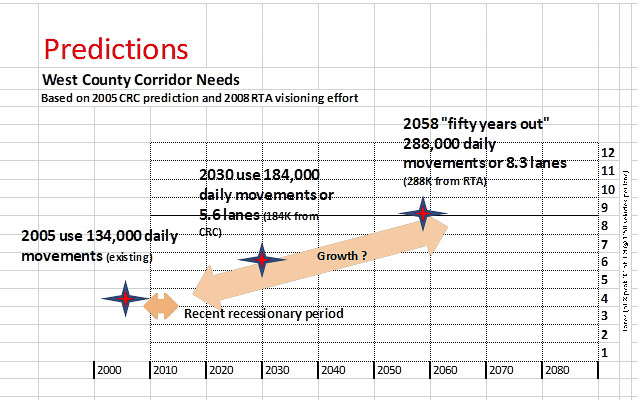

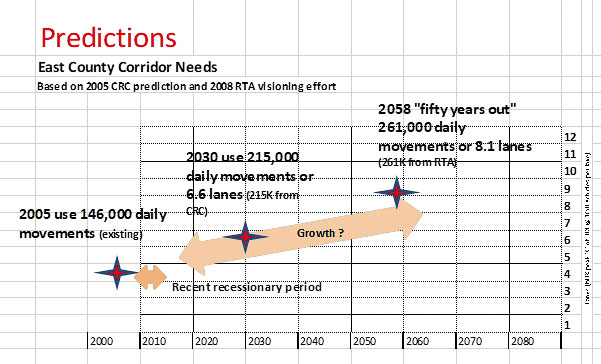

A new bridge should be expected to serve the community for 100 years or more. The two Washington traffic projection studies offered insight into the traffic needs for the next 20-60 years for both a west transportation corridor (I-5 region) and an east transportation corridor (I-205 region).

Corridor lane projections

Peterson converted the traffic projection data into a more easily understood metric — how many lanes would be needed to handle the traffic. He offered citizens a graphical presentation showing the existing lane capacity and the lanes needed as regional population and travel demand grows.

The current RTC traffic congestion report states the Interstate Bridge reached peak capacity in the early‐1990s; and the Glenn Jackson Bridge did so in the mid‐2000s. Prior to the pandemic there were in excess of 300,000 vehicles crossing the Columbia River on the two bridges daily.

For the western transportation corridor, currently served by I-5, Peterson said the RTC data showed 184,000 daily vehicle movements by 2030. That would require over five lanes in each direction. By 2060, the prediction was for 288,000 daily movements or over eight lanes in each direction.

Peterson doesn’t think Portland would be willing to accept an I-5 at the Rose Quarter that is wide enough to handle five or eight lanes at the Columbia River. He said the Rose Quarter was the “elephant in the room” with regards to dealing with I-5 corridor needs.

“I don’t think Portland can make that sort of gut-wrenching decision to introduce more cars into downtown Portland in the short term,” he said. Therefore additional transportation corridors are the logical alternative along with express bus transit, because the metropolitan area is evolving into a community of many urban centers, shifting from a Portland centric land use pattern.

“Once there is agreement as to the number of vehicles that will be accepted into downtown Portland through the Rose Quarter, then we know what to build across the Columbia River,” he said.

Two Washington studies projected traffic growth into the future, including the RTC “Visioning Study” from 2008. They showed 261,000 daily movements in east Clark County and 288,000 daily movements in west Clark County by the year 2060. Graphics from Kevin Peterson

To the east on the I-205 transportation corridor, the RTC data revealed there were 146,000 daily vehicle movements in 2005. They predicted 215,000 movements in 2030 and 261,000 movements in 2060. That equated to a need for over six lanes in 2030 and eight lanes in 2060.

Peterson reported that an east county bridge would reduce I-205 traffic congestion in the area of the Portland airport and I-84 by 15 to 20 percent according to the studies.

In total, the traffic projection numbers indicate an estimated 550,000 vehicle movements daily by 2060. That is an 83-percent increase from current traffic levels.

The role of transit

“You’ll find that transit advocates would say this future is solved if we just extend light rail,” Peterson said. “Unfortunately, a two-car train operating as a tram (MAX) in mixed traffic is the equivalent of one half lane of actual viability if you’re looking at how it would actually be used.” It is contrary to the fact that transit ridership has been in decline for over a decade.

TriMet’s MAX light rail trains are limited to two cars in a train, due to the length of a downtown Portland city block. This “half lane’’ capacity of the Yellow Line is barely adequate to serve North Portland and should be preserved for Hayden Island/downtown Portland users.

“There needs to be a fundamental revision of how transit is looked at, over the longer term,” he said. “That’s going to tell us, as a community, if we’re going to evolve into a true metro system.” In the short term, express buses can be used in the corridors.

If Yellow Line capacity (250 persons per train) were used by Clark County residents, the simple reality is there would be no room on the train for North Portland users.

“I cannot imagine commuters from Vancouver spending an hour standing in a train, passing through stations in north Portland in which you have to employ people with white gloves to shove the north Portland commuter on board, because there’s no room in these slow-moving trains,” he said, describing what happens in the Tokyo subway system.

Transit has to take on a completely different dynamic on the north I-5 corridor, according to Peterson. “The worst thing that could happen now would be to spend a couple of billion dollars on light rail that will not provide a lasting benefit.”

Peterson suggests policy makers should look at the bridge as a “transportation platform,’’ designed to anticipate future transportation solutions not possible with the CRC design. For example, any bridge built should have the ability to include dedicated lanes for bus rapid transit (BRT), which can be a decades-long interim transit solution awaiting Portland’s solution to the downtown rail bottleneck. In the future it could handle commuter rail, metro rail or readily integrate a variety of intelligent vehicles.

“Using a straight alignment and collector-distributor allows these modes, and more, to be readily integrated,” he said. Dedicating four general purpose express lanes plus two lanes for express transit fits the “cap’’ or restriction Portland has placed on downtown Portland through traffic. Four lanes for shore-to-shore arterial vehicle movement plus two lanes for local transit on the “collector-distributor” level serves the local needs of Vancouver and North Portland.

From a policy point of view, Peterson believes two things are at play. One is why a policymaker north of the border would be willing to spend Washington state taxpayer money without having that concurrency. The other thing which is more gut wrenching, is how is Portland going to deal with the car in the long term. “Quite frankly, that decision has to be made before a policymaker in Washington can comfortably invest taxpayer money,” he said.

Peterson shared that a straight bridge can be a beautiful addition to the region and cityscape. “It is much safer, has a significantly smaller environmental footprint and is less costly; all possible if a collector-distributor is considered,” he said.