Target Zero Manager Doug Dahl discusses driving in hazardous flooding situations

Doug Dahl

The Wise Drive

Q: We’ve been getting flooding alerts where I live. So far no flooding here fortunately (sorry to all the folks in flood areas), but I’m wondering, when there’s water over the roadway, at what depth does it become a hazard?

A: If I can take this in a direction that’s a bit off track from where you were heading, a lot less than you might think. Parts of western Washington are generating real-time evidence that flooding is dangerous for drivers (and pedestrians), but before we get to those depths, even a tenth of an inch of water could be too much.

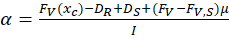

I’m talking about hydroplaning. If speeds are slow, you needn’t be concerned. Hydroplaning happens when you drive faster than your tires can displace the water on the road. Because of so many factors that contribute hydroplaning, there’s no magic speed threshold where it crosses from safety to danger, but there is some math that can get you close. It looks like this:

No, I’m not figuring that out either. But if you assume that the water is deeper than the tread depth on your tires, you can multiply the square root of your tire pressure (in psi) by ten and get pretty close to the best-case scenario speed (in mph) likely to result in hydroplaning. (For those who don’t want to do any math, it’s around 55 to 60 mph for a typical car). With the right (or wrong) conditions, it can happen as slow as 35 mph. Vehicle speed, volume of water on the road, tire pressure, and your tires’ ability to drain away water are all factors in hydroplaning. Of the four, drivers can control three. The correct tire pressure and sufficient tread depth on your tires reduces the risk. Choose a slow enough speed while driving and it’s preventable.

And what about actual flooding? Maybe you’ve seen recent pictures of stranded cars submerged up to their windows. That’s too deep, obviously, but is there a depth that’s safe to drive though? Kind of, but with a big caveat. First though, the standard guidance:

In still water, any water deep enough to get sucked in through your engine’s air intake is going to be a hard limit – your car will decide it for you when it quits running. And it might require a new engine. On some cars that could be as little as six inches.

Moving water is where things get serious. Six inches of rushing water is enough to sweep a pedestrian off their feet. Twelve inches can carry away most cars. Two feet of moving water can carry away SUVs and trucks.

Here’s the problem with offering those numbers; they’re not that helpful if you can’t tell how deep the water actually is. Flood water is dirty – just a few inches and you can’t see the road anymore. It might look like it’s shallow enough to drive through, but that’s probably what the folks who ended up in window-deep water thought too.

And then there’s what’s happening underneath the road. Rushing water can erode the ground supporting the roadway. From the perspective of the driver’s seat, that erosion will be invisible until the road collapses. You don’t want your car to be the proverbial straw that broke the asphalt camel’s back.

All this adds up to real consequences. The US averages 113 flood fatalities a year, and over half of those occurred when a vehicle was driven into flood water. Given all the unknowns when a road is covered with water, the smart move is, as they say, “Turn around, don’t drown.”

Also read:

- Opinion: Interstate Bridge replacement – the forever projectJoe Cortright argues the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project could bring tolling and traffic disruptions on I-5 through the mid-2040s.

- Opinion: Oversized tires and the frequency illusionDoug Dahl explains why tires that extend beyond fenders are illegal and how frequency illusion shapes perceptions about traffic safety.

- Opinion: IBR’s systematic disinformation campaign, its demiseNeighbors for a Better Crossing challenges IBR’s seismic claims and promotes a reuse-and-tunnel alternative they say would save billions at the I-5 crossing.

- Opinion: Is a state income tax coming, and the latest on the I-5 Bridge projectRep. John Ley shares a legislative update on a proposed state income tax, the I-5 Bridge project, the Brockmann Campus and House Bill 2605.

- Board authorizes C-TRAN to sign off on Interstate Bridge Replacement Program’s SEISThe C-TRAN Board approved the Final SEIS for the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program, with Camas and Washougal opposing the vote over light rail cost concerns.