Melody Pfeifer does not consider herself an activist.

“I’m a mother, a grandmother,” says the 59-year-old Cowlitz tribal member and coordinator of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe’s Youth Program. “I was never an activist.”

But when Pfeifer heard last August that Native American Indian tribes were gathering in North Dakota to stand with their brothers and sisters in the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Pfeifer says she felt called to action. Pfeifer and one other Cowlitz member joined those who had been protesting the massive 1,172-mile-long Dakota Access oil pipeline — a pipeline that Standing Rock tribal members say is wrecking sacred Sioux sites and threatening to destroy the critical Missouri River watershed, a drinking water source for the Sioux.

“For a lot of us, for a lot of tribal members, this is a passion,” Pfeifer says. “We are protecting our Mother Earth. We are protecting her for our children, for our people, for all people.’’

Along with Linda O’Brien, the wife of Cowlitz Indian Tribal Councilman John O’Brien, Pfeifer traveled to North Dakota in early September to join hundreds of other Native Americans protesting the oil pipeline through nonviolent resistance and prayer.

If construction continues, the $3.8 billion pipeline would transport domestically produced crude oil from North Dakota through four states and 50 counties, going underneath the Missouri River and ending in Illinois, where it would connect to an existing pipeline that runs to Texas. Proponents say the pipeline is crucial for helping the U.S. free itself from foreign oil dependence.

Opponents, including several international environmental protection groups such as Greenpeace, and the hundreds of Native American tribes who are gathered in North Dakota to support the Standing Rock Sioux, say the pipeline is an environmental ticking time bomb that could wipe out sensitive habitats and taint the Missouri River watershed indefinitely.

Pfeifer says the protesters are trying to protect the earth and save natural resources for everyone, not just for their own Native American people: “I thought about what’s happening at Standing Rock and around the country and tried to find an example of how many hearts’ feel,” Pfeifer says. “I thought of the World Trade Center [the 9-11] invasion on our homeland and the disregard for life. What was lost, we will never get back. The same goes for the water and sacred lands. We are the caretakers and the disregard for Mother Earth is devastating.”

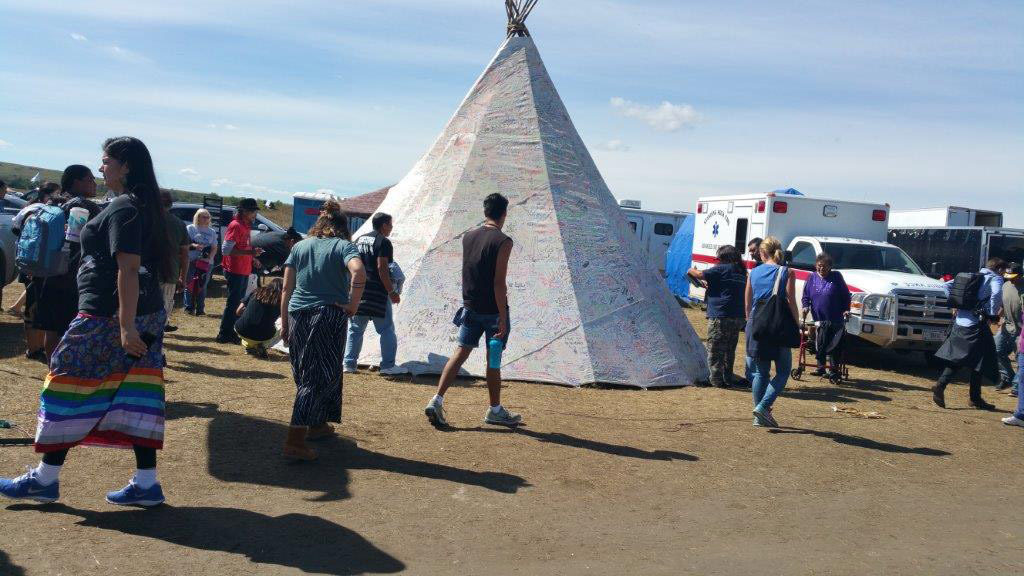

Despite traveling around police barricades, meeting others who said they’d been maced by pipeline security guards and attacked by the guards’ dogs, seeing surveillance helicopters overhead and knowing that North Dakota’s governor had deployed the National Guard to protect the pipeline construction, Pfeifer says she felt no fear during her eight-day stay at the Dakota Access pipeline resistance camps.

“It was very peaceful, very serene,” Pfeifer says. “For me, I had gone to help … but I found that I was the one who was blessed. It was a very spiritual experience for me. A life-changing experience.”

Before they left Washington state, O’Brien and Pfeifer packed supplies, food, the Cowlitz flag and O’Brien’s store of traditional spiritual medicines into their car. They left on Sun., Sept. 4, and traveled nearly 1,300 miles, finally arriving at the protest camps in North Dakota. When they got there, the other people at the camp were in distress — the day before, they said, pipeline construction workers had bulldozed a sacred Sioux burial site. The pipeline protesters — or water protectors, as they prefer to be called — were preparing for a sacred ceremony at the desecrated site.

“Linda had brought cedar, sage, lavender … spiritual medicines,” Pfeifer says. “And the day we got there was the day after they had unearthed the burial site, so we used all of her medicines.”

Although the two women had only intended to stay a couple days, they wound up staying for more than a week and Pfeifer says she would have stayed indefinitely, if she could have. But work with the Cowlitz tribe, and her own family, including her husband, son and two grandsons, called her home. Still, she says, it was hard to leave the Dakota Access protests.

“It was amazing, what was going on there,” Pfeifer says. “People were coming together with one common purpose and they were doing it peacefully. There were not fights. People got along. And they took care of each other.”

At night, young Native American men — known as warriors to the others at the camp — would patrol the camps on horseback, ensuring that the water protectors were, themselves, being protected.

“This (the pipeline protests) stemmed from the youth, you know,” Pfeifer says. “They want to have what their ancestors had. They know that they are the keepers of the land.”

Pfeifer says she has already made plans to return to the protest site and this time, she’s bringing two very special members of the Cowlitz tribe.

“I’m going in the spring and I’m planning to bring my grandsons,” Pfeifer says. “They’re 17 and 10 years old … and they really want to go.”

Other members of the Cowlitz tribe also are planning to join the pipeline resistance, including a midwife who will travel to the site in early November, Pfeifer says, to assist pregnant women who have joined the movement.

During her time at the Dakota Access pipeline resistance camp, Pfeifer worked in the warriors’ kitchen, feeding the young men and helping keep their strength up for their nightly vigils. Inside the camp, the Cowlitz women met members of Native American tribes from all over the country, traded stories with the other Native American women in their immediate camp area, talked to young warriors who had braved pipeline security forces who, they said, sprayed them with mace and unleashed dogs on their people.

They watched elders teach young children the customs of their tribes and were witness to two historical events: the coming together of the seven original Sioux tribes, also known as the seven Sioux Council Fires, and a meeting of the Sioux and Crow tribes.

“Neither of those things had happened since Wounded Knee,” Pfeifer says, referring to the 1890 massacre of hundreds of Native American men, women and children by U.S. federal forces near Wounded Knee Creek on the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. “It was amazing to feel the energy of the people who were there. No one was scared, even though we knew that the governor had called the National Guard out. The feeling from all the people was that we were safe, we would take care of each other.”

When word came that President Obama had issued a temporary injunction against construction of the pipeline, Pfeifer says there was rejoicing in the camp.

“People were crying and drumming and singing,” Pfeifer recalls. “But we knew it was just the beginning.”

This week, Pfeifer and her fellow and sister water protectors received some bad news: A federal appeals court in Washington D.C. had denied the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s request for an injunction to block the pipeline’s construction, opening up more construction near the Standing Rock reservation land in North Dakota. What’s more, on Mon., Oct. 10, a day many Native Americans and individual states celebrate as Indigenous Peoples’ Day instead of Columbus Day, 27 pipeline protesters — including Hollywood actress Shailene Woodley, star of the blockbuster, young adult movies “The Fault in Our Stars” and “Divergent” — were arrested for blocking pipeline construction sites.

“It was a stumbling block,” Pfeifer says. “But this isn’t the end. I have a feeling that more people will notice what’s going on now. I could see this going on for a long time, maybe for years. People everywhere are joining in … they are saying, ‘enough is enough’ and they’re fighting for their water, for their resources. This isn’t just about the Missouri River or about the Standing Rock Sioux: This is about all of us, about making sure that we leave our children, our grandchildren, our future generations, with the same resources we have now.”

To learn more about the Dakota Access pipeline protests, visit the Standing Rock Sioux’s site. Pfeifer says, with winter coming, the water protectors are going to need supplies to protect against fierce winds and freezing temperatures. The Standing Rock website has a list of needed supplies, as well as a PayPal link for those who wish to make a donation to the tribe’s efforts to block the pipeline.