The numbers come from the annual Point in Time count done last January

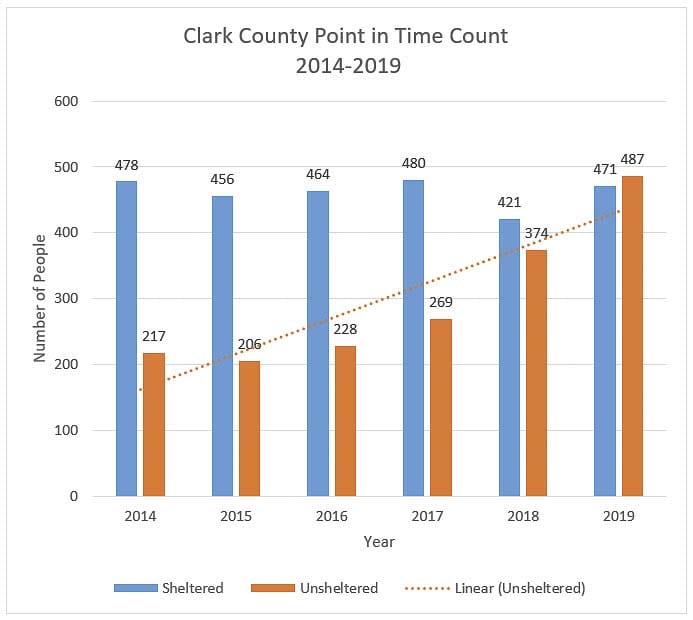

VANCOUVER — For the first time in at least eight years, there are more people living on the streets of Clark County than in shelters.

“It aligns well with the trends we’re already seeing throughout Clark County: that the numbers of people that are already experiencing homelessness, whether they’re sheltered or unsheltered, continues to rise,” says Kate Budd, director of Council for the Homeless which conducted the annual count January 24 with the help of 30 volunteers.

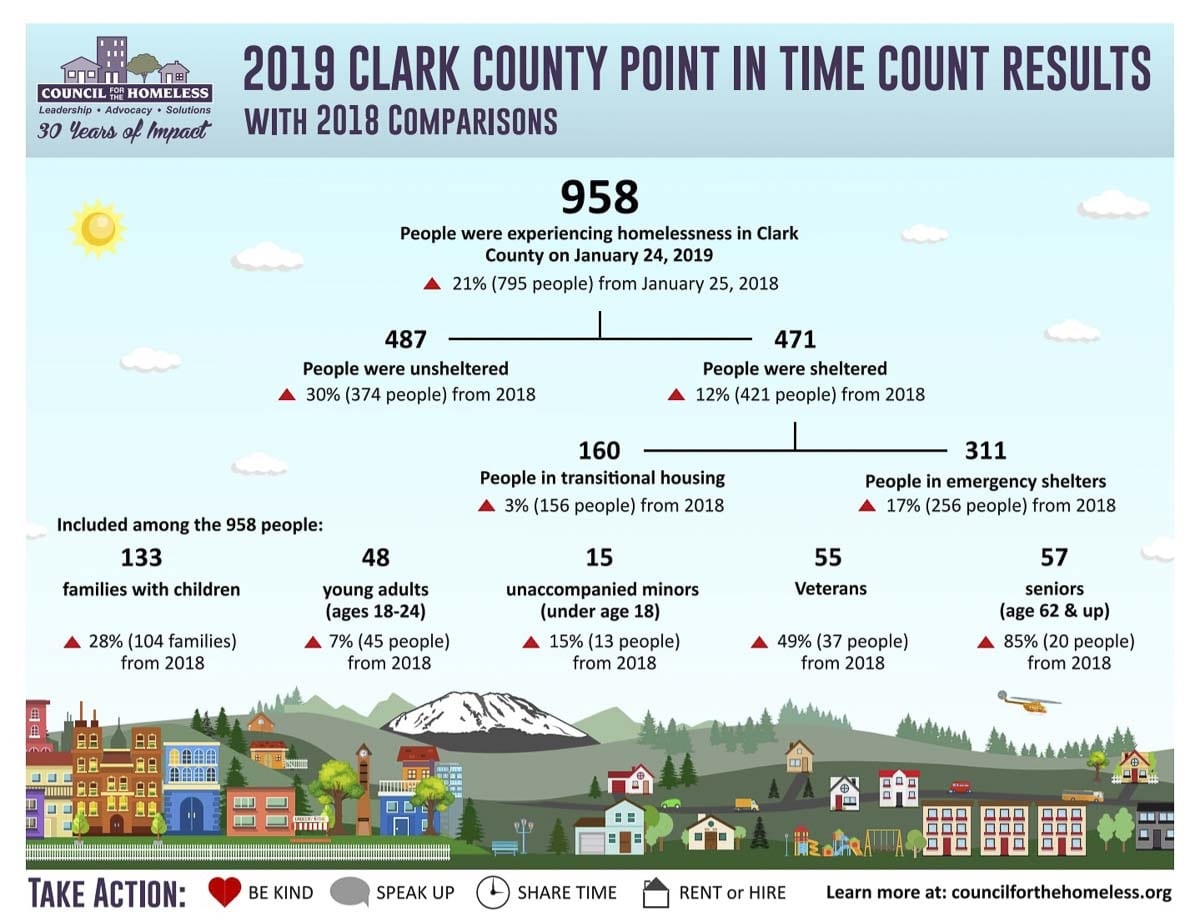

The Homeless Point in Time count data, released over the weekend, found a total of 958 people who identified as being homeless on some level. 471 of those were in either emergency shelters or transitional housing, a 12 percent increase. In their data, Council for the Homeless says that was due to an increase in hotel vouchers and emergency shelter beds due to severe weather on that day. 487 were living outside in tents, vehicles, or underneath an overpass. That represents a 30 percent increase over 2018’s count and 218 more unsheltered people than in 2017.

The 958 people located during the 2019 count represents a total increase of 21 percent over 2018 when volunteers talked to 795 people identifying as homeless.

“Over the full calendar year of 2018, 4,708 people representing 3,106 households identified as experiencing homelessness, according to the Council for the Homeless Management Information System (HMIS),” the agency said in a release, “which provides a much more robust and accurate count of homelessness. The amount of households experiencing homelessness according to HMIS grew by 20% from 2017 to 2018, confirming the trend seen in the PIT data.”

The Point in Time Count is mandated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as a snapshot of homeless populations across the country. It is conducted by volunteers on the ground performing a manual survey of people living in emergency or transitional housing, as well as tents, cars, RVs, and on the street. Given the nature of the survey, it is likely that actual numbers are higher, but the data helps to inform decisions when it comes to federal funding of housing and homeless programs.

Of those questioned in the survey, 37 percent indicated “lack of income” as their primary reason for being homeless and 17 percent cited a lack of affordable housing, followed by eviction at 15 percent.

“It all really circles around how the rents have increased so significantly,” says Budd. “We’ve seen, in the last five years, rents increase by $500. And we know that our incomes, whether you’re employed or you have a stagnate income like social security, they’re not increasing $500 a month unless you get some kind of a very large promotion.”

The story around homelessness, for many, revolves around a drug crisis running rampant on our streets. Eight percent of respondents who said they dealt with some form of disability as part of their homelessness cited substance abuse, but most cited physical or mental disabilities. Budd says the housing crisis also plays into the issues of drug and alcohol abuse on the street.

“Some people may have had a behavioral health challenge before they experienced homelessness, and it may have exacerbated whatever situation was going on,” she says, “but then there’s many people who may have become homeless as a result of a lack of affordable housing or eviction and then, simply as a matter of survival, turned to substance use because being without a home is really scary.”

Perhaps most startling of the numbers in the survey are families. Of the 958 respondents, 47 percent were families with children. Of those, 59 were unsheltered.

“They’re living in cars, they’re living often in places that are not meant for habitation — an outbuilding or in a garage with no plumbing, or in an RV,” says Budd. “And we see that very often in our housing solutions center and know that our schools are seeing that on a regular basis, and that families are really struggling.”

Of those in the survey, 45 percent were female, and 16 percent were chronically homeless and 79 percent said their last home address was within Clark County, while five percent had come from Portland. Twenty-three percent were black, in a county where they make up just 13 percent of the overall population.

“There’s no one that’s immune to homelessness, whether it’s in this community or beyond, the Point in Time count really shows that,” Budd says. “There was a really high percentage increase among seniors which is, of course, very concerning and unfortunate.”

Fifty-seven people in the survey were 62 or older, an increase of 85 percent from 2018 says Budd. Veterans are also experiencing a sharp rise in homelessness with a 49 percent increase over last year.

To Budd, the Point in Time count shows that traditional stereotypes of homelessness no longer apply in post-recession America.

“These are families, these are seniors who are in their 70s and 80s, these are women with physical disabilities and people with behavioral health challenges that all just need additional support so that they can have somewhere affordable to live and meet their basic needs,” she says.

Budd says programs like the city of Vancouver’s Affordable Housing Fund are making a difference as more people are able to either get into housing or keep from losing a roof over their head. The state legislature also passed a bill this session that allows cities or counties to assign part of their sales tax to spend on affordable housing and rental assistance.

The Point in Time count is used by cities and counties across the country as a reference for housing and homelessness assistance grants and as a way of determining the success or failure of homeless programs.

There is some debate over this year’s count. It is the first time volunteers used a new app called Counting Us, allowing them to go away from paper surveys.

“It was met very positively, and really well regarded among those who were counting that morning and throughout the day,” says Budd.

But the count also came two months after Vancouver Police had worked to disperse a number of homeless camps in downtown Vancouver, so outreach workers had some difficulty in finding where many of the area’s homeless had gone.

“It’s valid that there were some folks who might not have been counted because of the police activity, but what I do not know is whether that police activity was any different from any other year,” says Budd, who adds that the results of the final count seem to reflect the reality their volunteers are seeing in the county.