Data from Clark County Public Health and the state’s Department of Health often don’t line up. So, what’s going on?

VANCOUVER — As the COVID-19 pandemic has dragged on, public health officials have found themselves increasingly questioned over just how they’re tracking tests, cases, and deaths.

The current pandemic marks the first time in modern history that governments have attempted to track a viral outbreak in near real-time.

Outside of localized outbreaks such as measles, tuberculosis, or other notifiable diseases, the analysis of a nationwide viral outbreak, such as the common flu, is done well after the fact.

While a test for the flu is common, doctors are not required to report a positive diagnosis to public health officials. Disease burden estimates are based on an extrapolation of data from a handful of hospitals, doctors, and public health agencies who are part of the FluSurv-NET reporting database.

It should come as no surprise, then, that questions surrounding how the COVID-19 pandemic has been tracked are frequent, and sometimes laced with a tinge of public distrust.

In Clark County, as elsewhere, amateurs tracking the pandemic have frequently raised questions regarding differences in data at the local versus state level.

At the time of this writing, Clark County Public Health (CCPH) lists a total of 3,799 confirmed cases of COVID-19 since the pandemic began, as well as 60 deaths blamed on the virus. Washington state Department of Health (DOH), meanwhile, lists 3,601 cases and 69 fatalities.

So what’s going on?

In part, it has to do with the way healthcare providers and labs report test results.

While many send test results electronically to DOH using the Washington Disease Reporting System (WDRS), other labs send, via fax, test results to Clark County Public Health, which then inputs the data into WDRS.

But it can take a while.

“For those sent via fax, we have to enter them manually into our database and enter them into the state database,” says Marissa Armstrong, a communications specialist with CCPH. “So those sent via fax may be a little more delayed in getting to DOH, since we have that extra step of manual entry.”

That data entry can be further delayed due to the fact the primary focus of CCPH right now is contacting new cases and doing contact notifications, before updating data for the state.

“It’s important to recognize the large burden that COVID-related data entry and reporting puts on our whole public health system,” says Michelle Osmanli, communications manager with the state Department of Health. “COVID has highlighted the underfunding of public health, and this is an example.”

That issue has, at least on one occasion, caused a backlog of cases at DOH.

On Sept. 25, the state issued a notification that they were adding 486 cases to Clark County’s total. Clark County Public Health said at the time they had reported those cases to DOH. In their statement to Clark County Today, Osmanli noted that there may be further discrepancies that still need to be cleared up.

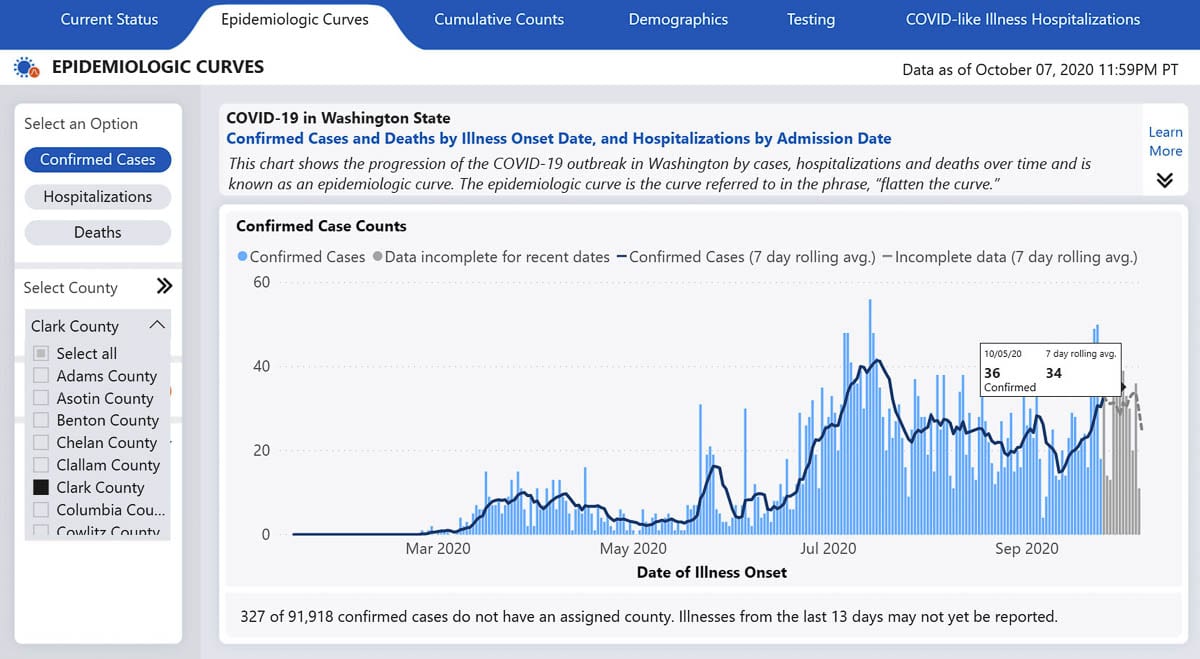

It’s also worth noting that the state’s epidemiological curve graph on the DOH Data Dashboard shows cases by date of symptom onset, while CCPH uses the lab test verification date.

The state noted their Cumulative Count tab likely trends closer to Clark County’s daily count, though varying case reporting cutoffs for each organization and differences in the timing of case notifications can still lead to variations in the data.

Both agencies said they are continuing to work on determining why CCPH has a death count of 60, while DOH’s total is nine higher.

Osmanli mentioned the state’s total includes “confirmed, suspect, and probable COVID deaths,” while CCPH has indicated they count only deaths in which COVID-19 was confirmed to have been a contributing factor.

Armstrong also confirmed that some cases are removed from the total if it is later determined that the individual lives outside of the county. In general these aren’t noted publicly, unless the data cleanup affects a larger number of cases, or results in the removal of a death from the total.

Total cases versus active cases

Another point of confusion has been the daily case count, versus what the county has termed “Active Cases.”

An active case is defined as someone who is still within 10 days of symptom onset, or who has not gone 24 hours without a fever.

Delays in testing, Armstrong noted, can mean someone with a presumed case who is currently self isolating ends up testing positive shortly before they are no longer considered an active case. In a handful of cases, a positive test result has come back after the individual was no longer considered contagious.

That explains why you can have over 250 new cases in a 7-day window, but active cases remain well below 200.

“The active case count is a point in time count and reflects the number of people in their isolation period – how many people are in their isolation period on this specific day,” wrote Armstrong. “New cases over the past week are, of course, cumulative and reflect those individuals whose positive lab results were reported to us this week.”

Since people often don’t seek testing until they experience symptoms, and it can take a day or two to get tested, and then several more days for results, it’s possible for a person to no longer be an active case before they even knew for sure they were infected.

This may change in the near future, as higher testing capacity locally could increase the speed for results, leading to more rapid detection of new cases, and the ability to test close contacts of confirmed cases to detect individuals who are asymptomatic.

Understanding the limits of contact tracing

Currently, Clark County has five teams of eight people working under a contract with The Public Health Institute of Oregon to help reach close contacts of known cases.

The goal is for a nurse with CCPH to reach a confirmed case within 24 hours, and then for close contacts to be notified within 48 hours of that diagnosis.

That goal has been complicated by testing delays. If a confirmed case is nearly over their sickness before they know they were sick, case investigations can be difficult.

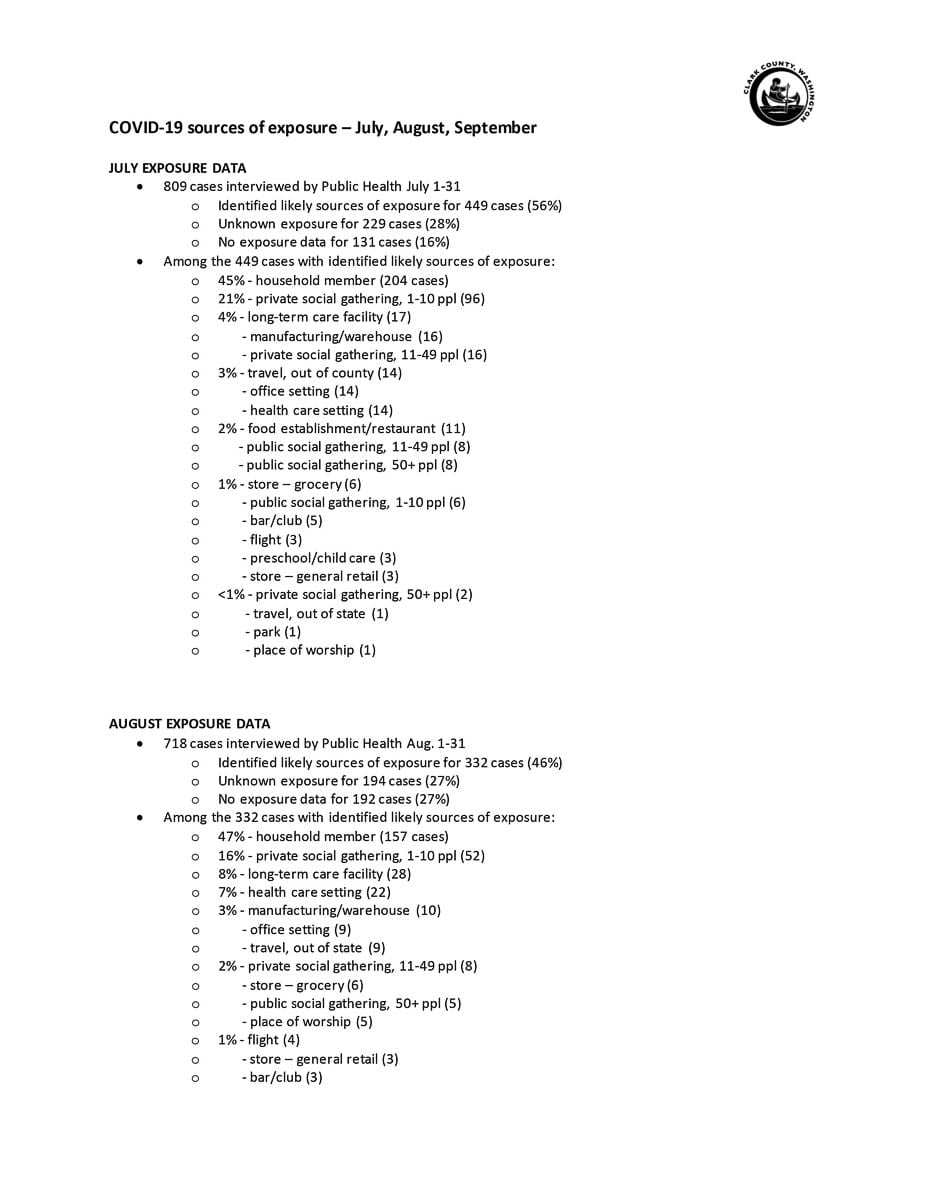

According to case investigation data released by CCPH covering July through September, a total of 2,294 cases were interviewed. Of those, data was unavailable for 538 cases, or 23 percent. That could mean the individual could not be contacted after multiple attempts, declined to be interviewed, or was simply not asked where they may have contracted the virus.

“There could be a variety of different reasons why we don’t have data on a specific person,” said Armstrong. “In some situations we may be speaking to a caregiver or a spouse, if the case is not well, or is hospitalized. So we may be speaking with someone on their behalf, who doesn’t have that information.”

In another 27 percent of cases, no exposure site could be confirmed, according to the county’s data.

That doesn’t mean the individual being interviewed has no idea of where they might have been exposed, says Armstrong, just that the county couldn’t link their case to another known infection.

“We need to know that our current case had contact with a known case, while they were contagious at that location,” Armstrong told Clark County Today. “And that’s a pretty high threshold. We’re not just saying, ‘Oh, they were at this restaurant, so that must have been where they got it.’”

In the simplest terms, that means the county only confirms a case as being linked to a restaurant, grocery store, church, or social gathering if another known case emerges from that location or event.

One example cited by Armstrong is the Orchards Tap outbreak in late June and early July.

“The customers there, they did not have any other known exposure,” she says. “But they were all in the Orchards Tap. And in the Orchards Tap we also knew that there was a confirmed case at that location as well.”

In other cases, there may not be a known single individual at a location who has tested positive, but if several other cases link back to that place, investigators could be reasonably certain someone there was spreading the virus.

“We need to know that they were in contact with someone who is contagious at a location,” says Armstrong, “or we need to have multiple cases kind of tied to the same location at the same time, with no other known exposures.”

Failing that, the origin of a case is listed as “unknown,” until or unless more infections emerge linked back to a location.

Of the roughly 2,300 cases investigated between July and September, public health was able to determine a likely infection source in 1,141 of them, or just under half.

Out of those, 45 percent of cases were transmitted through the home.

During the measles outbreak in 2019, 87 percent of cases were spread between members of the same household.

To public health officials, that means community transmission of COVID-19 is much more prevalent.

As for where that community spread is happening, nearly 28 percent of cases were linked to social gatherings, with the vast majority of those coming from small, private gatherings of 10 people or less.

In September, six percent of cases were linked to private social gatherings of between 11 and 49 people, up from four percent in July, and just two percent in August.

It should be noted that the data does not break down far enough to know how many cases could be linked to a single gathering, or a handful of them.

Long term care facilities and healthcare settings were the next most likely place for COVID-19 transmission, with an average of 12 percent of cases linked to those types of locations during the three months, including 15 percent in August.

While a handful of cases could be linked to restaurants or grocery stores, the requirement for people to wear masks seems to generally be limited exposure for most people.

Restaurants accounted for less than two percent of known COVID exposures, while grocery stores averaged the same, topping out at 12 cases in September.

The contact notification contract with Public Health Institute currently runs through October, but Armstrong said CCPH is planning to seek an extension through Dec. 30 from the Board of Public Health and the Clark County Council.

A note about schools

While Clark County’s current rate of new COVID-19 cases puts us firmly in the high risk category for school reopenings, many districts are moving ahead with plans for a transition to hybrid in-person learning as soon as mid-November.

In preparation, Clark County Public Health has launched a new website where they are listing cases linked to schools throughout the county. The case information includes the date infection was confirmed, whether it was a staff member or a student, and whether the exposure happened inside of a school building.

Currently, Evergreen School District has had nine confirmed cases, all among staff, and no exposures inside their buildings.

Battle Ground Public Schools had three cases linked to Prairie High School, including one in the building, though no other known cases have been linked back to that individual. Another case at Pleasant Valley Middle School involved a staff member who was not in the building.

Vancouver Public Schools has reported two cases in staff, neither of which worked in a building.

Camas and La Center schools have each reported one case in a staff member, with no building exposure.

For private schools, Cornerstone Christian Academy reported two cases, including one student, with no exposures inside the buildings.

A student and two staff members at Kings Way Christian school tested positive, though no exposure was reported in the building.

To view the full list, click here.

For more information on the county’s response to COVID-19, click here.