A bridge too low was one of many reasons Columbia River Crossing failed in 2013

A week ago, the Executive Steering Committee (ESC) of the Interstate 5 Bridge Replacement Project was reminded by the Coast Guard that a new permit is required. Legislators from both Oregon and Washington have set in motion a process to use what was done in the failed Columbia River Crossing (CRC) effort to now attempt to build a replacement Interstate Bridge.

Critical to that decision was the fact that $140 million federal dollars was spent in the earlier effort. They must either resume construction of a bridge project or pay the funds back. Oregon used $93.3 million in federal highway money while Washington used $46.1 million.

Steven FIsher is the Coast Guard Bridge Administrator and was listening to the online meeting. During public comments Fisher told the ESC the following. “I wanted to just make sure everyone knew that the Coast Guard permit that was issued back for the CRC is expired. A new navigational impact study will have to be done to determine the correct horizontal and vertical clearances.”

That is hugely important. In the original CRC battle, the bridge height was a critical factor. It was described by one media source as a “high stakes limbo dance.”

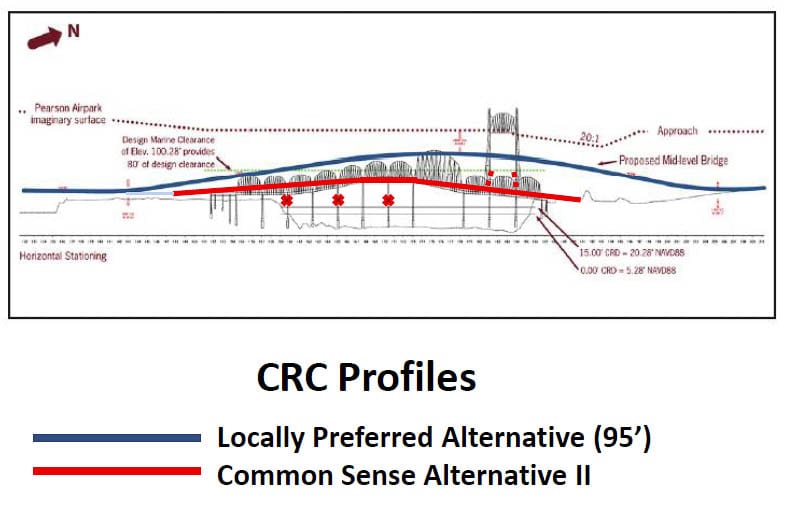

The original proposal was a bridge with 95 feet of clearance above the water. That wasn’t high enough for some Columbia River ships. CRC officials went ahead in spite of warnings from Coast Guard officials.

A second proposal came forth with 110 feet of clearance. But that was not what the Coast Guard indicated was needed.

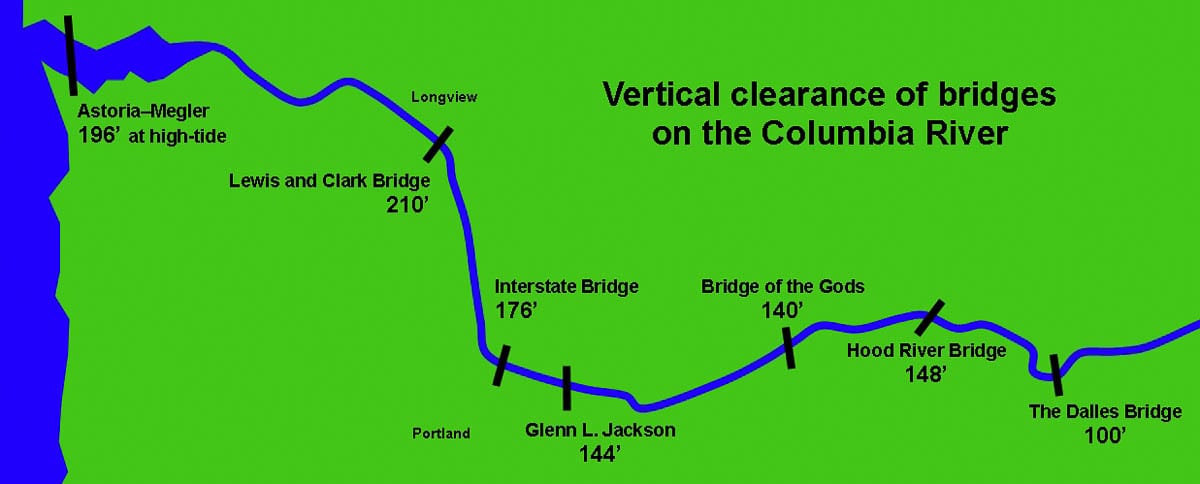

The current Interstate Bridge, when lifted, goes to 178 feet; the Glenn Jackson Bridge clears 144 feet. A mid level bridge (with 95-to-110-foot clearance) has “a low probability of meeting the reasonable needs of navigation or of obtaining a Coast Guard permit,” wrote D.A. Goward, the Coast Guard’s marine transportation director at the time.

One ship that wouldn’t be able to operate under that CRC design was the Yaquina, a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dredge that needs 116 feet of clearance. The CRC suggested the Corps buy a smaller dredge, contract out dredging to private companies, or shorten the Yaquina’s height according to one news report.

The Columbia River is regularly dredged by the Army Corps of Engineers to keep the navigation channel accessible, especially for the ports of Portland and Vancouver. Every year the Corps dredges six to eight million cubic yards of sand from the 107-mile shipping channel between Astoria and Vancouver. About one billion cubic yards have been excavated since the Corps began maintaining the shipping channel more than 90 years ago.

Politics came into the equation as multiple Coast Guard Administrators/Commanders weighed in. Many citizens believed people were fired or “retired” until someone was appointed who would approve a lower bridge height.

Coast Guard Rear Admiral K.A. Taylor pushed back on multiple issues. One news report highlighted the problems.

“The Coast Guard is concerned that subsequent river analysis has shown that the 2004 boat survey data informing the choice of alternatives was not comprehensive,” Taylor wrote.

“As previously noted, there may be over one hundred vessel transits per year impacted by the mid-height bridge being reviewed that were not accounted for in 2004. Current and potential future river users must be taken into consideration when determining the reasonable needs of navigation.”

A January 2013 letter from Congresswoman Jaime Herrera Beutler put further emphasis to the low bridge height. In the letter lawmakers highlighted navigation and commerce worries for river users upstream of the proposed project.

“We cannot cavalierly dismiss the impacts to the businesses, current and future, which depend upon the free flow of river commerce to survive,” the letter reads. “Neither can we dismiss the impacts to our local economy, nor the jobs that would cease, should these companies be forced to relocate or close their doors.”

The final version had 116 feet of clearance and did receive Coast Guard approval. However that low bridge height required “mitigation” for three up river businesses. Their largest products would not fit under the proposed 116-foot bridge. John Rudi of Thompson Metal Fab said: “We had notified CRC as far back as 2006 that we were looking for at least a 125-foot clearance.”

The CRC reached agreements that would have paid the three firms a combined $86.4 million. Thompson Metal Fab was to receive $49.8 million. Oregon Iron Works would have received $11.8 million and Greenberry Industrial would have received $24.8 million. At one point, Oregon Iron Works sued the CRC regarding mitigation.

Many pushed for a bridge height of at least 125 feet. Others pushed for the 144 feet of the Glenn Jackson Bridge on I-205. A CRC analysis at the time said a 125-foot clearance would add $176 million to the project’s price tag. Adding even more to the height would require a new design and environmental study process, as well as reconstruction of parts of downtown Vancouver and the North Portland Harbor it was reported.

The Coast Guard never said how high a bridge must be. Clark County Today reached out to Fisher, the current Coast Guard Bridge Administrator.

“On 27 September 2013 the USCG permitted a Bridge (previously known as CRC) that was never built,’’ Fisher wrote in an email response. Condition 10 of that permit said “The approval hereby granted shall cease and be null and void unless construction of the bridge is commenced within three years and completed within five years after the date of this permit.”

The bridge was never built and the 2013 USCG permit is null and void as per condition 10 of the 2013 USCG Bridge permit.

“The team overseeing this project (applicant) will need to apply for a new U.S. Coast Guard Bridge permit,’’ Fisher said. “In 2016 the USCG published its latest Bridge Permit Application Guide (BPAG). Any new bridge permit request will need to be submitted IAW the 2016 BPAG. There is not a modified process. Here is a link to the BPAG.’’

Fisher offered more insight into that process.

“The majority of the time is taken with the applicant compiling the application documentation IAW the BPAG,’’ Fisher said. “The application consists of environmental compliance documentation and documentation to establish the needs of navigation compliance. The time it takes to compile the application is dependent on the resources the applicant dedicates to permitting compilation.’’

Once the application is deemed complete (all documents are complete and IAW the BPAG) the Coast Guard will issue their Permit Decision within 90 days of a NEPA Record of Decision being issued (in accordance with EO 13807, if applicable), if the application is complete at that time. If the project uses another level of NEPA documentation, the permit decision will be issued 3-6 months after receipt of a complete application.

Fisher was then asked if there is a minimum height a new bridge must have in order to obtain approval?

“Horizontal and vertical navigation clearances are determined by an analysis of the Navigation Impact Report (NIR) that is compiled by the applicant as described in the BPAG,’’ Fisher said.

Here are the steps to determining navigation clearances:

1. Applicant sends a project initiation request IAW BPAG to USCG

2. USCG asks applicant to conduct a NIR IAW BPAG

3. Once USCG receives the completed NIR from the applicant the Coast Guard will analyze the NIR and make a Preliminary Navigation Determination (PND) which will prescribe the horizontal, vertical and other navigation requirements a new Bridge would need to comply with.

4. The applicant would take the USCG PND and start their NEPA alternatives design analysis.

“The USCGs primary concerns will be to ensure that the proposed bridge meets the reasonable needs of navigation for the expected life of the bridge and that all NEPA environmental control laws are complied with,’’ Fisher said.

Given the turmoil in the failed CRC effort around the bridge height, citizens will surely be watching to see what the current effort will propose for a bridge height.

Greg Johnson, the Program Administrator of the Interstate Bridge Replacement Project, told the Executive Steering Committee Nov. 6 he had hired WSP USA as the primary consultant because they had been involved in the failed CRC.

“I take it as they understand what the process was and where it failed and why it failed. So bringing that and being unshackled by the history of the past project is going to be tremendously important,” Johnson said.