Nancy Churchill explains why just getting a hearing is progress in Olympia

Nancy Churchill

Dangerous Rhetoric

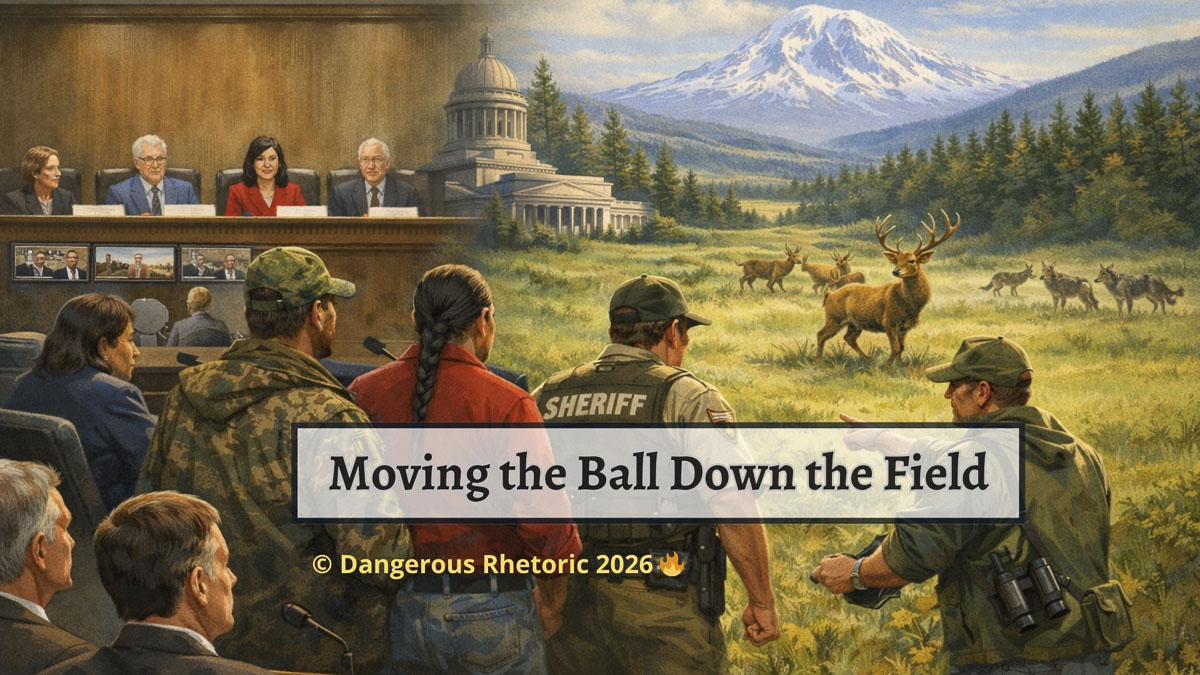

In Olympia, success is often measured in blunt terms. Did the bill pass or fail? Did it get out of committee or die quietly on the calendar? That scoreboard mentality misses how real change actually happens, especially on complex, politically charged issues like wildlife management. Sometimes progress looks less like a touchdown and more like moving the ball down the field one hard-fought play at a time.

That is exactly what happened with HB 2221, the bill to restore and sustain healthy ungulate populations in eastern Washington.

HB 2221 will NOT advance out of the House Agriculture and Natural Resources Committee this session. It’s easy to become discouraged by that failure to advance.

However, what happened in that hearing room was not a loss. It was a win, and an important one, because it forced a long-avoided conversation into the open, built new relationships, and laid the groundwork for a durable, science-based solution to an ecosystem that is badly out of balance.

At its core, HB 2221 was a modest bill with a disciplined purpose. It did not call for predator eradication. It did not declare war on wolves. It asked for balance, accountability, and timely action when science tells us something is wrong.

The bill created a clear, enforceable framework to restore deer, elk, and other ungulate populations in parts of eastern Washington where wolves are already federally delisted. It did three simple but powerful things.

First, it is defined when a herd is “at risk” using an objective metric: a 25 percent decline below its ten-year rolling average. That matters because it removes the fog of ambiguity. No more endless debates about whether a decline is “significant enough” or whether more study is needed. Data, not ideology, triggers action.

Second, it required the Department of Fish and Wildlife to act within 60 days once that threshold is crossed. Not study forever. Not convene another task force. Act. Predator mitigation would no longer be optional or indefinitely delayed while prey populations continue to collapse.

Third, it restored transparency and collaboration by mandating annual population surveys and public reporting, with direct involvement from sportsmen. Reports would be due before hunting seasons are set, not after decisions are already locked in. Trust cannot exist without timely information, and rural communities have had too little of it for too long.

The bill also recognized something Olympia often forgets: eastern Washington is not western Washington. Ecosystems differ. Geography differs. Human communities differ. HB 2221 applied only to the federal delisting area, respecting the reality that one-size-fits-all wildlife policy does not work across a state this large and diverse.

Most importantly, the bill tied success to real-world outcomes people understand. Predator mitigation would continue until mule deer and white-tailed deer met or exceeded 2004 harvest levels for two consecutive years and exceeded their ten-year rolling averages. Clear benchmarks. Measurable recovery. Accountability everyone could see.

Those policy details mattered, but what truly moved the needle was the hearing itself.

On paper, HB 2221 looked like the kind of bill that gets quietly buried. It challenged entrenched habits inside an agency. It questioned discretionary delay. It forced uncomfortable conversations about predator management. Traditionally, bills like that draw overwhelming opposition from outside the district, drowning out local voices.

That did not happen this time.

Instead, the 7th District showed up.

People drove for hours. They testified in person and remotely. They signed in electronically in numbers that stunned the room. Sportsmen. Conservationists. Tribal representatives. County sheriffs. A county commissioner. Private citizens. Hunters. Wildlife advocates. Cattlemen. People who live with the consequences of policy decisions made hundreds of miles away.

When the tally came in, it told a story Olympia could not ignore: 760 in favor, 386 opposed.

Those are not the numbers of a fringe issue. Those are the numbers of a constituency demanding to be heard.

Just as important were the voices themselves. Testimony made clear that deer and elk are not abstract symbols in Ferry and Okanogan counties. They are the prey base that supports predators. They are the backbone of hunting cultures that treat stewardship as a responsibility. They are an economic engine that sustains guide services, outfitters, fuel sales, lodging, and sporting goods stores in communities with few alternatives.

When ungulate populations collapse, the effects ripple outward. Predators turn elsewhere. Ecosystems destabilize. Rural economies suffer. The science is clear, and the lived experience of frontier communities confirms it.

The hearing did something else that matters even more in the long run: it opened doors.

Chair Kristine Reeves agreed to continue working on the issue over the interim. Representatives Hunter Abell and Andrew Engell committed to developing a new bill for next session. Senator Shelly Short plans to work towards a joint House-Senate Agriculture Committee meeting. Conversations began that had not happened before, with people who had not been in the room together before.

That is how change happens in Olympia. Not by shouting from opposite sides of a barricade, but by keeping the conversation going, building relationships, and asking policymakers to see the land, the scale, and the people affected by their decisions.

Plans are already underway to invite both House and Senate committee members to Ferry County this summer. Not for speeches, but for a tour. From Nespelem to Keller to Republic and beyond. From tribal lands to working ranches to wildlife corridors. To see the size, scope, and beauty of the district and to understand what ecological imbalance looks like on the ground.

This is not surrender. It is a strategy.

If you care about science-based wildlife management, rural economies, and honest stewardship, HB 2221 did exactly what it needed to do this session. It moved the ball down the field. Politics is people, and relationship building is how we advance the issues we care about.

The scoreboard will matter later. For now, the win is that the game is finally being played in the open, with the people most affected back in the huddle. Many thanks to all the Ferry, Stevens, and Okanogan residents who testified on this important bill. Your efforts to testify on HB 2221 made a difference, and we will continue to work to move the ball down the field.

Nancy Churchill is a writer, educator, and conservative activist in rural eastern Washington State. She chairs the Ferry County Republican Party and advocates for effective citizen influence through Influencing Olympia Effectively. She may be reached at DangerousRhetoric@pm.me. The opinions expressed in Dangerous Rhetoric are her own. Dangerous Rhetoric is available on Substack and X.

Also read:

- POLL: Will lawmakers’ actions at Tuesday’s State of the Union Address impact your voting in the upcoming mid-term election?Clark County Today’s latest poll asks voters whether lawmakers’ conduct during the State of the Union will influence their mid-term election decisions.

- Letter: Endorsement of Eileen Quiring O’Brien by retired Major General Gary MedvigyRetired Major General and former councilor Gary Medvigy outlines his reasons for endorsing Eileen Quiring O’Brien in the Clark County auditor race.

- A bill giving AGO ‘enormous amount of power’ clears House committeeSenate Bill 5925 would expand the Washington Attorney General’s authority to issue civil investigative demands without a judicial warrant.

- Clark County Council discusses resolution on unityClark County councilors debated a proposed unity resolution, with questions about redundancy, enforcement and community input before moving it forward.

- Clark County Council Chair Sue Marshall will not seek reelectionSue Marshall announced she will not run for reelection to the Clark County Council, citing family, farm life, and other priorities as she completes her final 10 months in office.